I find it hard to imagine pursuits more important than becoming the people we ought to be.

A philosopher might ask where this “ought” comes from and why heeding it is important. A project manager would simply ask for tools to get the project done.

This article belongs to the latter mindset. I’m just one guy sharing the spiritual tools that have worked for him. I did not invent any of these, and they are all ancient. They stem from the faith tradition I grew up with, but here I express them in the language of this productivity and knowledge management community we find ourselves in. It wouldn’t surprise me if you have received the same tools through a different lineage.

The focus of this article will be on practices that can be used in Roam. I imagine these practices can be repurposed for whatever spiritual growth means for you.

These thoughts lead on to an interesting question: can software actually help you grow spiritually? Let’s explore this question first before we talk about individual practices.

Computer-aided Spiritual Growth

Technology aiding spirituality is not a recent phenomenon. The technology of writing on paper has become so ubiquitous that it doesn’t feel like technology. But, if we imagine ourselves at a time before widespread literacy and access to paper, we can better see how they have changed the game. We have a civilization-wide amnesia of memory techniques.

The church I belong to has a process of vetting the holiness of a person. These vetted saints are held up as examples of pathways to holiness. For instance, if your work is to speak truth to power, you have the example of Catherine of Siena. If your pathway is to find sanctity in overcoming trauma, you have Josephine Bakhita.

Is there a saint whose path includes a note-taking tool for thought? It may be too early if we define “tool” as software, but if we consider pen and paper to be an earlier version of this, then we have many. For note-taking in particular, we have Josemaría Escrivá, who saw his life’s calling while organizing his notes.

Source: opusdei.org/en-ph/article/the-founding-of-opus-dei

This was just with notes on paper. Isn’t software-assisted thinking simply a more powerful pathway to the same endpoint?

It is easy to forget this inside our little bubble, but most of the world live perfectly happy lives without note-taking or tools for thought. But if you use software for thinking about your work, why not also use it for your spiritual life?

Roam aids thought, including the thinking part of spiritual growth

The first attempts at using software for thinking were simply translations of paper tools: notes, mind maps, canvases.

The fun began with the creation of thinking tools that are hard or impossible without computing: Anki, spreadsheets, Twitter as inter-mind API, Roam.

Spiritual growth is not purely an intellectual pursuit. Yet, it has aspects that rely on thinking. For instance, many faith traditions offer sacred scripture as pathways to enlightenment. If you are given a tool that helps you grapple with these texts, wouldn’t it accelerate this pursuit?

Another aspect of spiritual growth is changing ourselves and the world around us. This requires reimagining reality and coordinating work between your past and future selves. An example (discussed more below) is habit building—reimagining your character, and training yourself towards this new you.

These two aspects—changing what you know and changing reality—are two common use cases of Roam. If Roam could be used for academic work and task management, what’s stopping us from using it to study our faith—as well as planning and executing matters of the spirit?

The Spiritual Growth Stack

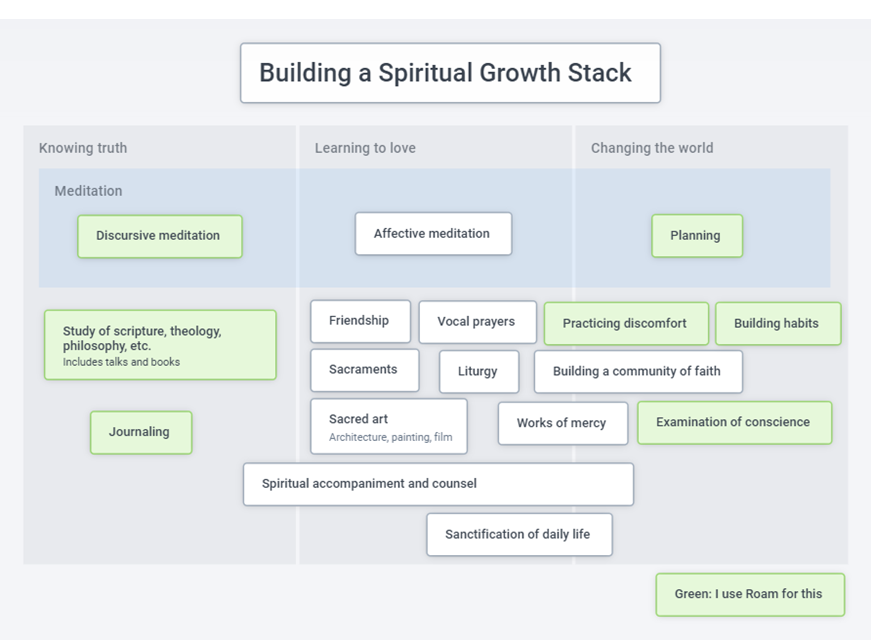

We each have our productivity and knowledge management stacks, our toolkits for knowledge work and project management. What would happen if we use the same mindset for spiritual growth? Here’s my attempt at a canvas for building a spiritual growth stack:

Made with Plectica: plectica.com/maps/H45EYHXHJ

The middle column, Learning to love, exposes the Christian roots of this concept map, but Knowing truth and Changing the world are probably applicable to most spiritual worldviews. These two outer columns also happen to be where I find Roam to be useful, and is what I cover in this article.

Tools you can try on your Spiritual Growth Stack

This is how I use Roam for the spiritual life. I won’t be sharing screenshots, as these are too personal. However, this shouldn’t be a problem as I am using Roam’s most basic features for these practices.

Meditation

Meditation spans the three aspects of spiritual growth. I use Roam for what is traditionally called discursive prayer, and what can be described as (spiritual) planning.

Planning. Many of us use a list of questions that we answer every morning, to guide how we will use the day. Elevating this to prayer is to try to see what is God’s will for me today. (If I were an atheist speculating on why this could work better than just choosing the day’s plan by myself, I’d probably think that modeling an all-wise and all-loving supreme being in my head would lead to more wise and more loving outcomes in planning.)

Here are some questions I answer in my morning prayer:

- What is the top thing I need to do for work?

- What is the top thing I need to do for family?

- What is the top thing I need to do for friends?

- What is the habit I need to reinforce today?

- How do I practice discomfort today?

The last two are examined in further detail below.

I mapped this kind of prayer in the Spiritual Growth Stack under Changing the world because change is the result of action, and action starts with thought. Thought is better when done deliberately, in meditation.

I have very recently changed my gratitude prompts from “thank you for x” to the following, after listening to this Art of Manliness podcast episode on Naikan, a Japanese method for self-reflection. We’ll see how this goes.

- What have I received from x?

- What have I given to x?

- What troubles and difficulties have I caused x?

The other kind of meditation I do with Roam is what is traditionally called discursive prayer. I do this in a similar way to how I wrestle with academic content. I normally translate a statement into a question, which I then answer.

For instance, a common question I ask myself when using scripture for prayer is “given this, what should I change in my life or in my mind?”. I find this process much more exhausting than reading technical papers, probably because papers have a focused scope, while this kind of prayer requires me to access my entire life, and look at it from the outside.

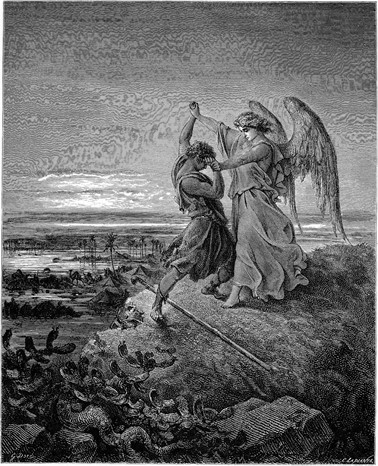

This is what discursive prayer feels like.

Gustave Doré, Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (1855)

I did this almost daily last May, fueled by that momentum you get when Roam finally clicks, but also through discipline. I’ve since stopped this effortful engagement. I want to associate my prayer with friendly conversation rather than combat. But I continue doing this at least once a month, when I attend the recollection organized by my church group. I’m the weirdo in the chapel hunched over his laptop!

It turns out there are many styles of meditation, even just within the Christian tradition. But this style, which admittedly tends toward the cerebral and practical, has been working for me.

Affective meditation can also be done in Roam, but I can’t bring myself to do it. Affective prayer is moving the will towards love for God and neighbor. Written down, this is like a love letter to God. Many spiritual classics sound like they are affective prayers. See Augustine’s Confessions and Thomas à Kempis’ Imitation of Christ, for instance.

Building Habits

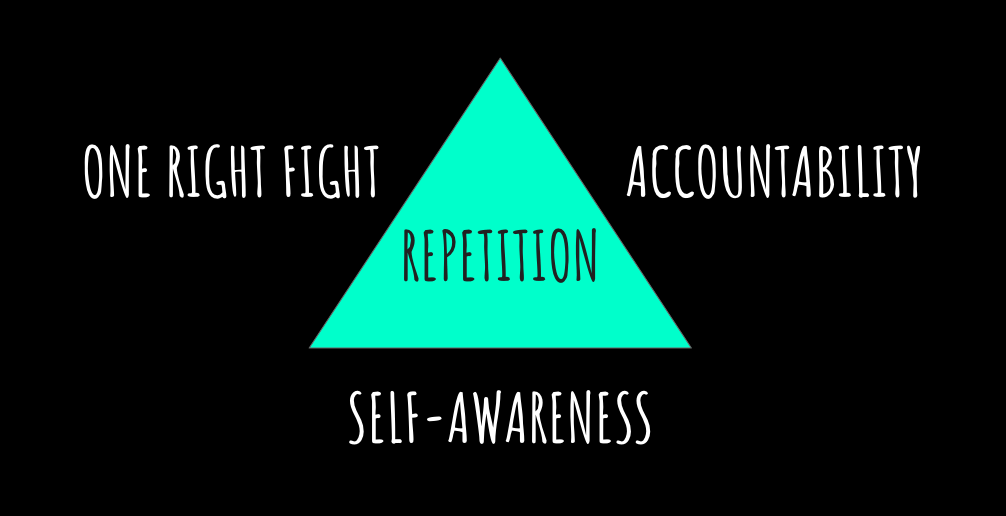

Changing the world starts with changing oneself. In concrete terms, that means building good habits and undoing bad habits. The system that has worked for me involves daily repetition supported by focus, accountability and self-awareness.

Source: medium.com/life-tactics/my-top-5-tools-from-20-years-of-building-and-destroying-habits-74debc5aeca5

Meditation takes care of self-awareness. A community, a small group of like-minded friends or a spiritual director, takes care of accountability. Choosing one particular habit—your one right fight for the week—takes care of focus.

I make that choice daily during my morning meditation by answering the question, “what is the habit I need to reinforce today?”. In Roam, I type in (( plus my prefix for these habits to bring up a selection (except for the first time, when I create the block). This allows me to easily be reminded of my focus and at the same time deliberately make the choice.

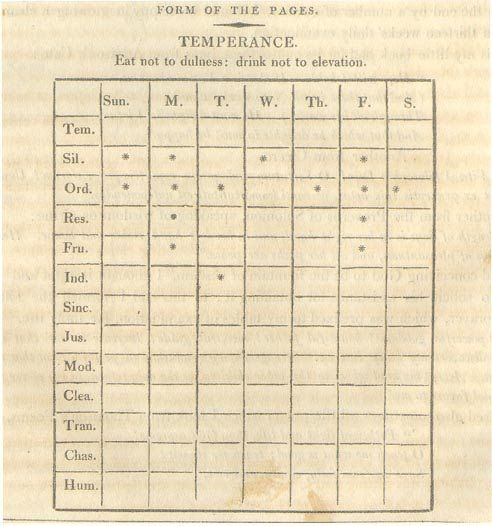

In my teens, I used to have a checklist similar to this card from Benjamin Franklin. These practices I list here each occupied a row, and the columns were the numbers 1 to 31, for each day of the month. If you google “roam habit tracker” you’ll find ways to do this in Roam.

After a few years, these practices become second-nature. This is an application of B.J. Fogg’s adage “design trumps willpower” in living one’s faith. These practices act like guideposts for living this life I want to live. But these guideposts need maintenance. I occasionally need to focus on regaining the rhythm or the quality of each of these practices.

The classic framework for habit-building are the four cardinal virtues, which would be familiar to followers of Stoic philosophy. Spirituality without human virtues often ends in tragedy. As C.S. Lewis said, “of all bad men, religious bad men are the worst.”

I wrote a longer piece about habit building here: medium.com/life-tactics/my-top-5-tools-from-20-years-of-building-and-destroying-habits-74debc5aeca5.

Practicing Discomfort

Practicing discomfort will also sound familiar to those who follow Stoic philosophy and those who train for a sport. The first step in building a new habit or getting work done is to overcome inertia. Overcoming inertia or generating the willingness to do hard things is a muscle that can be trained. This training involves practicing discomfort.

These are small, unnoticeable things. I try to choose things that help me do my work better (eg, limit Twitter to certain times of the day) or things that make me less annoying to the people around me (eg, trying to be cheerful around friends and family even when I’m not in the mood). Like the habit I focus on for the day, I type in (( plus the prefix I use for this to bring up a list to choose from.

Since I do this in the context of my faith, I see this as more than just a way of growing in self-mastery. Following Christ also means carrying the crosses in my life. The little discomforts of work and family life are the most abundant sources of these small but constant encounters with Christ. If you want to know more about this, just google “mortifications,” which is what this practice is called in Christian asceticism.

Reviews

This is called “examination of conscience” in my faith tradition. I try to remember the day’s habit during the quick midday examination of conscience (which, for me, takes less than a minute). I do a slightly longer one a few hours before bed (3-5 minutes). This nighttime examination is a review of the day, in which I focus on gratitude for the good things and sorrow for my faults—and maybe note some improvements for the next day (at least this is the ideal).

I don’t use Roam for my daily reviews. This is like using a chainsaw when all I need is a knife. But I do use Roam for the longer examinations during my monthly recollection, which takes a few hours, and my yearly retreat of a few days. A key practice that helps in these longer reviews is to collect questions that can help prompt insights during these deeper examinations of conscience. I tag questions that surface during my daily meditations and from the books I read, for use during recollections and retreats.

Journaling

Many saints journaled their way to spiritual growth. For instance, the most influential book of Ignatius of Loyola, “The Spiritual Exercises”, is based on his spiritual journal.

There are many styles of journaling. Here’s a video of some Roam users sharing how they journal in Roam.

RoamStack has top level notes on the different styles of journaling shared in this summit: gratitude journaling, emotion tracking, evening reflection, and being more mindful in decision-making—practices we have seen in other parts of the spiritual growth stack.

Morning Pages is my preferred journaling style. Morning Pages is from a book called The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron. It is a daily practice intended for increasing creativity. It involves writing three pages of raw unrestrained sentences every morning. I use it off-label for expunging unwanted emotions, like anger or anxiety, or for escaping a loop of rumination. And I only do it when I need to.

In Roam, I set up {{word-count}} and {{[[POMO]]: 25}} to count the words and create a Pomodoro timer. I then try to hit 750 words as fast as I can.

Study of scripture, theology and philosophy

Spiritual growth can come from living the customs and following the rituals of ancient traditions. If you are someone who uses your intellect to make a living and to make sense of the world (you most likely are if you are visiting this website), then shouldn’t your spiritual growth be intellectual as well?

Ancient faith traditions and practical philosophies like Stoicism have texts that have passed through the filter of time: the Bible, the Tao Te Ching, Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, etc. For millennia, the best tools we had for grappling with these texts were pen and paper. Now we have Roam and other tools for thought, which use the power of computing to aid our biological brains, just like power tools aid our biological limbs.

The conversation on #roamcult Twitter might give the impression that the most important features of Roam are the latest shiny ones. But like most things in life, Roam’s fundamental features provide most of its value.

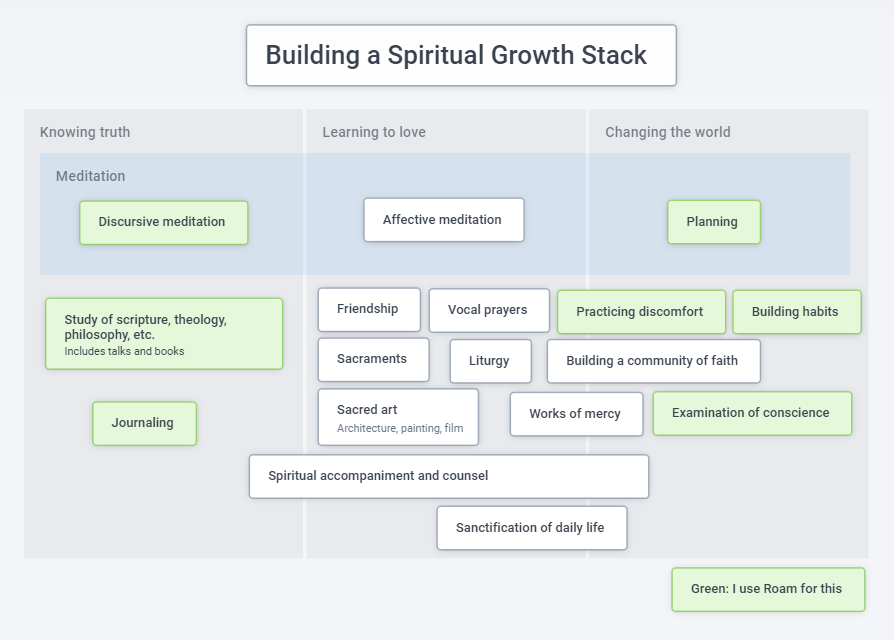

The blog posts written here about academic work suggest sophisticated ways of using Roam for extracting and wrestling with ideas stored in texts. What I want to highlight here are a couple of features that we seem to take for granted: the sidebar and copy-dragging blocks (with automated referencing).

The best features are often those that make you wonder why nobody has done them before. For years, we accepted the solution of placing a PDF or website in a window at one side of the screen and copy-pasting and alt-tabbing to a word processor on the other side. With Roam, your primary text, its commentaries and your own synthesis can be put in one screen, each collapsible, and each consisting of blocks that can be moved and copy-dragged around. There is no going back after experiencing this.

These features that help us deal with academic text also help us in the intellectual part of spiritual growth: understanding ideas from foundational texts and changing our minds as we grapple with them.

The Longest Game

Your cosmic world view, whatever it is, presents you with an ideal self. Perhaps that ideal is a more loving you, a more disciplined you, a more adventurous you. I look back to my teenage self, before I started these practices, and this is my testimonial: they worked for me. That testimonial though is dwarfed by the testimonial of history: how long these practices have accompanied humankind, and how many spiritual traditions carry them.

I’ve only been using Roam for a few months, but my experience has given me confidence that computing power can be used to support these practices. If you believe, as I do, that we have souls that transcend space and time, then anything that could help us grow spiritually is worth exploring. Incorporating these practices into our lives takes work and many cycles, but they are definitely worth it. This is the longest game we could play.

____

Thanks to Tracy Winchell and Paul Stadig for reading and giving feedback on earlier versions of this article, and to Francis Miller for the great editing, as always. If this article resonated with you, I’m happy to discuss or answer questions. Tag or DM me at @roamfu on Twitter.