(This article originally appeared on Drew Coffman’s website and is re-published here with his permission.)

One of the reasons that I’m finding so much success with Roam can be summarized in a single idea from a book I just finished (and highly recommend) called How to Take Smart Notes by Sönke Ahrens:

Your note library is not an encyclopedia. It’s a tool to facilitate thought. Don’t worry about completeness. Only write if it helps you with your own thinking.

Notes as a full summary

When I wrote that down, I realized that up until this point I never really understood that. In the past I have always tried my best to capture a complete experience in reference to the things that I was taking notes on.

I would try to write notes that gave a full summary of whatever input I had found. If I was reading, I would find myself highlighting almost everything of relevance, attempting to add it all into my notes in some meaningful way so that I could reference it later.

This is a really, really good way to burn yourself out.

It’s not sustainable, and even if it was, it’s definitely not pleasurable!

To try and ‘capture it all’ every time you come across something of interest doesn’t work for long — and you also can’t rely on your own memory to remember it. There’s another lesson from the book about that. Research shows that we are severely limited in what we can remember, holding a maximum of somewhere around seven things in our mind at any time.

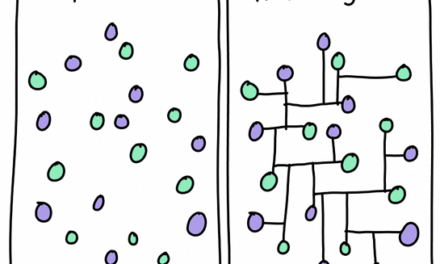

Notes as connections

The trick that memory artists use to remember more is not by somehow upping the amount they can actually remember, but by bundling information in meaningful ways. The funny thing is that we might all actually do this — the true number for what we can hold in our mind may be closer to four than seven, but we are so accustomed to bundling our thoughts that any research is tricked into giving us a higher number.

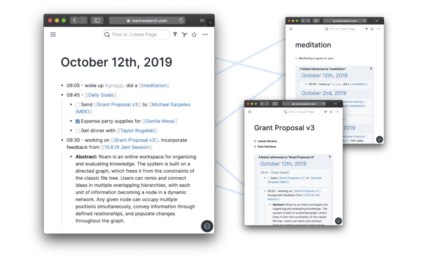

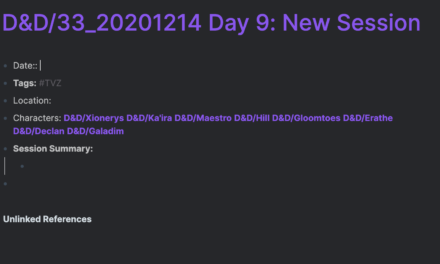

Since our brains are extremely limited in space, information floats freely about always looking for a place to land. When it does, it immediately derails us and demands our attention. This is why it’s vital that we close any mental paths that are open. Our ability to connect (or bundle) information is a massive skill that we are very, very good at, and Roam helps you get in the habit of bundling, of connecting, or offloading.

All of the things that your brain is constantly looking to do, Roam does better — and it does it while simultaneously changing my focus to connecting my thoughts instead of capturing input. Changing that focus means, ironically, that I’m capturing more input than ever.

When I read an article that I like or a chapter in a book that’s interesting, my first thought is ‘How can I connect this to the rest of the notes in my collection’ instead of ‘How can I make this note stand on its own, as an island, capturing everything important about it right now?’.

It’s obvious in retrospect, but connecting notes to the rest of my thoughts makes them so much more memorable and relevant in my mind! I’m more likely to reference them, to remember them, to write more, to think more, to connect more!

I am able to let go of the mental weight of thinking about what I’m finding, and offload it to my collection in Roam.